“I come here to learn my mother tongue. And it is easier for me to speak with my elders and my grandparents,” says 13-year old Melissa Dhakal. She is one of the 57 students who fill four classrooms in Milson School in Palmerston North every Friday evening to learn Nepali.

Dhakal’s parents, like those of most other kids in the language class, are former refugees who live in Palmerston North.

In the late 80s and early 90s, Bhutan adopted policies that discriminated against the Nepali-speaking “Lhotsampa” community in the southern part of the country. Their language was removed from the school curriculum and traditional Bhutanese attire was made compulsory, in an attempt to assimilate the Lhotsampa into Bhutan’s dominant culture.

Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International records say resistance from the Lhotsampa was swiftly and brutally put down.

New life in a new country

Tens of thousands of people who either fled or were evicted from Bhutan crossed over the border into India and subsequently into Nepal where they lived in refugee camps built by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) for close to two decades.

An entire generation grew up in these refugee camps, stateless and with no rights to work or travel outside the country.

A resettlement program facilitated by the UNHCR that started in 2007 saw more than 112,000 Bhutanese refugees resettled in different countries around the world, with a majority of them being accepted by the United States.

The first Bhutanese refugees to be resettled in New Zealand came here in 2007 and the community’s number has grown since then to more than 800. A majority of them live in Palmerston North.

Munu Karki, whose daughter has been attending these classes for some years now, says language and culture are important markers of identity for these children. She is from Nepal herself but her husband and in-laws initially came there from Bhutan. “When they (children) meet their relatives who live in different parts of the world, they shouldn’t need an interpreter,” she says.

Learning the script

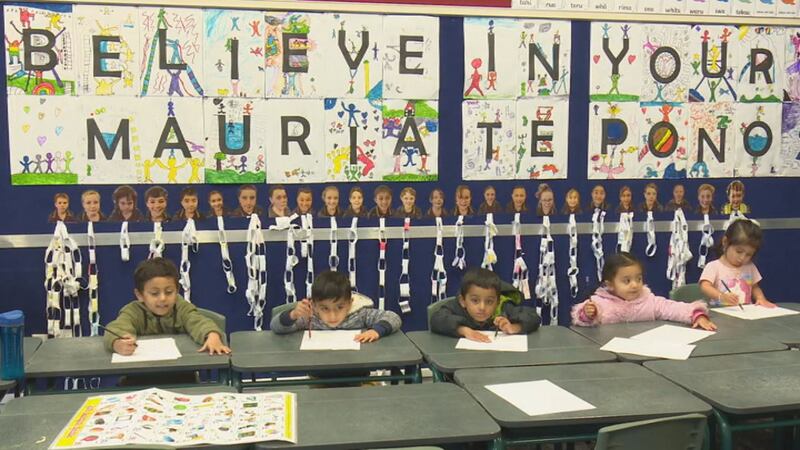

“Last year there were 75 students,“ Nepali language class head teacher Govinda Regmi says. “This year we are slightly low in number. I think there are around 57 students. But we have younger ones coming in as beginners, so I can see this number consistently going up,” he says.

And while the students are learning to speak and doing so with fluency, aided by their families who use the language at home, reading and writing in a script that is very different to the one they are used to (the Latin alphabet) can sometimes be a challenge.

But it is necessary, says Melissa Dhakal. “Since my grandparents are overseas, I can write them letters and they will understand,” she says.

Fourteen-year old Niraj Ghimire says learning to read Nepali also helps him connect with his religion, primarily because the language uses the Devnagari script which is also used to write Sanskrit- the language of Hindu scriptures. “My parents are very religious, as am I,“ he says. “So I get to read them the Gita, which is our holy book.“

‘We are succeeding’

The Bhutanese Society of New Zealand is also “thankful to the Ministry of Education that provides funding and to the principal and management of Milson School for providing the classrooms,” Regmi says.

“Our aim is for the children to be able to carry out basic conversation, so when they grow up and want to acquire fluency, they don’t have to start at the bottom,” he says. “So far, we are succeeding at that, and even exceeding expectations.“