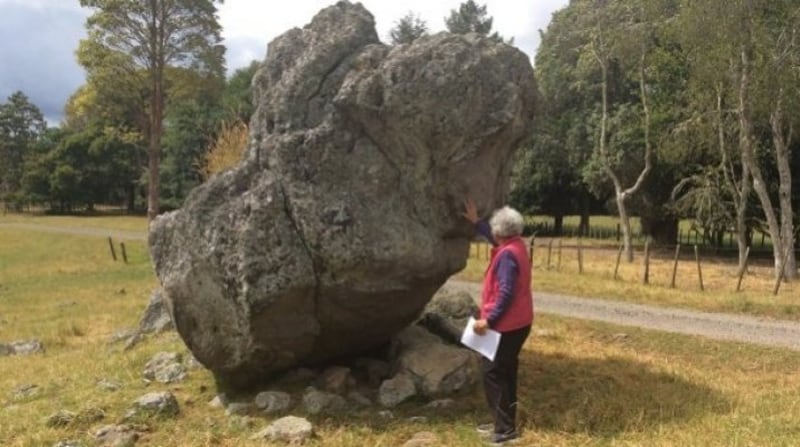

Bella Tari with Te Tino a Taiamai. Bella originally proposed Te Tino o Taimai for listing as a Wahi Tapu.

A significant landmark in the Bay of Islands, held in high regard by Māori, has been officially recognised by Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga as a wāhi tapu.

Te Tino a Taiamai is a prominent rock sacred to the hapū of Taiamai of Ngāpuhi. It has now been added to the New Zealand Heritage list.

The Heritage Pouhere Taonga Act defined wāhi tapu as places sacred to Māori in the traditional, spiritual, religious, ritual or mythological sense.

Heritage New Zealand’s Maori Heritage Adviser, Atareiria Heihei collated the research from a variety of written and oral sources for the listing proposal.

She says, “Te Tino a Taiamai stands about 3m tall and is located in a clearing just south of the township of Ohaeawai,”

The rock became associated with a mystical bird after the conquest of the Taiamai plains by an alliance of Ngapuhi hapu around 1790. It was named because Kaitara – one of the chiefs of the conquering hapu – declared it to have come from “beyond the sea” (“tai a mai”).”

Legend says the inhabitants of the area are said to have caught sight of a large and beautiful white bird that circled around in the sky before settling on the rock. The bird then proceeded to sip the rainwater from the small pools created by indentures on top of the rock - just as many birds do today.

“The arrival of the bird is said to have prompted immediate speculation about the nature of this tohu [sign] and whether it was of divine origin,” says Atareiria.

When Kaitara was called he was amazed at what he saw, and in one account said:

“My people, this beautiful bird has come from Hawaiiki and is a welcome guest that has been wafted inland by the winds of Tangaroa, the god of the sea. Therefore let us call him Taiamai. He will be our bird and I declare him tapu, do not venture near, but view him from afar, he will bring us great mana.”

Every afternoon Taiamai would settle on the rock to sip water from one of the pools, and the presence of the bird is said to have added greatly to the mana of Kaitara and his people in the eyes of other tribes.

“This fame was a double-edged sword as Taiamai’s fame spread around the area, and attracted the jealousy of a neighbouring rangatira who set out to capture the bird for his own purposes,” says Atareiria.

“One evening the rangatira came to capture the Taiamai, in the process violating the edict that Kaitara had put in place declaring that the bird was to be left alone. Rather than be captured, however, the bird vanished by melting into the rock and was never seen again. The rangatira fled, fearful that a maketu [curse] would be placed on him as a result of his actions.”

In some accounts, a dying rangatira later travelled to visit Te Tino o Taiamai and sat gazing at the rock in meditation for many hours and that after his death it was said that his spirit had fused into the rock with that of the Taiamai bird, further increasing its tapu nature. Another account says the rangatira was the guilt-stricken would-be thief.

“In any case, Kaitara named the stone Te Tino o Taiamai which is said to be an abbreviation of the phrase ‘Ko te Tino o Taiamai tenei kamaka’ – which means ‘this is the precise spot / the essence of Taiamai’,” she says.

The Taiamai is said to possess its own mana tapu or sacred influence and over the years became an uruuru whenua – a place at which travellers deposited small offerings; generally small pieces of vegetation. Travellers would also recite karakia to clear their spiritual path through the area.

Its location on the north-south, west-east ‘crossroads’ between the Hokianga, Bay of Islands, Aupōuri Peninsula and Waiomio and Whangarei reinforced its importance as a tapu stone with its prodigious mana.

Located within an area known as Tupe Tupe – meaning ‘clearing’ – the land around Te Tino a Taiamai was one of the first blocks of land in the region to be sold to Europeans. Early European visitors like Samuel Marsden and the artist Augustus Earle were impressed by the fertile soils as well as large-scale cultivations of kumara, potatoes and corn.

The block of land was sold to Henry Williams of the Church Missionary Society in 1833.